Is "encourage" the best the state can do? How about "help" or "support"?

After offering several paragraphs about initiatives that focus on "recruitment and admissions policies" being undertaken to diversify the developing teacher force, the article lays out possible reasons for the under-representation of racial minorities.

The article initially suggests that the biggest impediments to building a more diverse teaching force are perceptions of and attitudes toward the teaching profession itself and education's general commitment to diversity. From Mitchell Chester, state commissioner of elementary and secondary education, we hear that "Our society, unfortunately, doesn't hold teachers in high esteem." Then we hear the arguments for and against the importance of the teaching force's being racially diverse: while some educators insist on the power and value of students' being taught by teachers with whom they can identify and to whose achievements and values they can aspire, other educators hold that "top-notch teaching . . . trumps other factors."

"Top-Notch Teaching"

So what leads to "top-notch teaching," and can we say that the teacher education courses and programs in which we want nonwhite college students to enroll can produce it? Can produce it single-handedly? In my book, top-notch teaching is the result of a combination of the following factors, at least:

- knowing one's content well--and continuing to deepen and expand that content knowledge;

- becoming instructionally skillful--and continuing to develop one's repertoire of instructional skills and ability to use those skills in the "right" instructional contexts;

- becoming skillful in terms of assessing students' knowledge, learning styles, strengths, weaknesses, understandings--and in terms of using that information to support the learning of students as individuals and in groups;

- being skillful at knowing and working with students as learners and people, and at working with parents, supervisors, colleagues, and students themselves to help those students achieve their learning potentials, pursue/reach their achievement goals, and develop the confidence associated with authentic learning and achievement;

- being part of an educational organization that provides the time and space to take advantage of and contribute to colleagues' skill and knowledge--and to be a genuine community in spirit and practice.

But this article talks about college programs -- and this is where we need to be really honest about who gets hired to teach in most Greater Boston schools. As the person who ran the New Teacher Induction Program at Cambridge Rindge and Latin School for many years, I can say that most of our new teachers, the majority of whom have been white and female, came to us with one or more of the following: a master's degree in education or the academic field in which they were teaching, several years of teaching experience in another secondary school, multiple years of teaching experience in a college, and/or multiyear experience in another profession or in the arts. Very tough competition for a teaching candidate with no teaching experience and a college degree only--unless a district is truly dedicated to supporting and bringing along a new teacher who oozes potential for continued learning and passion for teaching in the public school setting.

The Financial Challenges of Teaching

But supporting and bringing along can't consist solely of mentoring and encouraging: that's simply not enough, especially for newly minted teachers who are graduating from college with loans to repay and who are entering Massachusetts public schools. For MA teachers, there is the expectation that they will earn a master's degree or the equivalent to advance from Preliminary to Initial licensure and/or from Initial to Professional licensure, according to guidelines set forth by the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. Such programs always have some cost.

Considerations of the economic situations and working-life realities of early-career teachers, especially early-career teachers in Massachusetts, are not considered in the article. While perceptions of value are almost always tied to economics in the U.S.A., the principal economic problems faced by those who choose to become teachers are not problems of status, whether the teachers are white or nonwhite. Most teachers I know chose the profession because they wanted to help kids and thought they'd enjoy doing so, not because they wanted to be admired. That said, they all appreciate being respected and don't always feel respected.

I also want to be clear here that I am making some assumptions here, for the sake of this blog post. There are no doubt African-American, Asian, and Hispanic college students who, because of scholarships and/or familial wealth, graduate from college without student loans and who can anticipate graduate study that will not put them into significant educational debt. I am choosing to focus here on nonwhite college graduates (by the way, I could be saying the same things about a significant number of white college graduates) who anticipate paying off loans for college, graduate school, or both for a number of years--and certainly while their salaries are relatively low. Given more general data about the economic categories in which racial and ethnic groups generally fit in America, I am also surmising--but without any proof--that African-American and Hispanic college graduates may be disproportionately represented among Americans needing to pay back college loans.**

So let's look at Cambridge, located so near to so many institutions that educate aspiring and practicing teachers. Yes, it's true that the Cambridge Public Schools has a Tuition Reimbursement Program, that the Harvard University Extension School offers some scholarships to public school teachers enrolling in courses, and that many online and face-to-face graduate programs are competing for educators in terms of the affordability and convenience of the programs they offer. But when one considers the cost of living in the Greater Boston area, even the economic support such programs offer does not significantly offset the loan-related financial burdens young teachers walk through the door shouldering. As one of this year's new teachers, a transplant from Texas, told me as we were talking about master's programs to which she might apply, "Teachers generally don't need master's degrees in Texas"--which means they don't have to pay for them.

But it's not just loan debt that makes prospective teachers wonder if they can afford to choose teaching as a profession. With or without loans, economically independent younger teachers wonder how far from Boston and Cambridge they will need to live if they wish to own homes of their own. As one transplant from another state asked me a few years ago, "Will I have no choice but to live with roommates when I'm forty-five?" Even yesterday, a Facebook Cambridge-educator colleague who came to CRLS six or seven years ago, now the father of two, posted a comment about how discouraged he was by his recent forays into the housing market. Other teachers have come to discuss whether they would have to downsize the families they planned to have, based on their experiences of providing for the needs of one child.

Interestingly, while I was reading the Boston Globe article today, I was simultaneously listening to an NPR/WGBH "On Campus" feature about Parent-Plus Student Loans. It incorporated the story of a proud mother who gladly incurred more than $130,000 in debt to

finance the educations of her two sons--and who expects to work hard

forever to pay back the money she borrowed. Despite her pride,

responsibility, and dedication, it's definitely not a story of planning for her own post-employment future at any point.

Interestingly, while I was reading the Boston Globe article today, I was simultaneously listening to an NPR/WGBH "On Campus" feature about Parent-Plus Student Loans. It incorporated the story of a proud mother who gladly incurred more than $130,000 in debt to

finance the educations of her two sons--and who expects to work hard

forever to pay back the money she borrowed. Despite her pride,

responsibility, and dedication, it's definitely not a story of planning for her own post-employment future at any point.As a middle-class white person who entered the teaching force in a very different economic time with a good education and a master's degree in tow, with manageable education debt to repay, and with parents who helped me out when I needed to buy my first car and my first condominium--and did so without subjecting themselves to great economic pressure or hardship, I have been economically and educationally privileged. But at the same time my parents were in the "safety cushion" background of my life as a young educator, I became aware that a number of my colleagues, both white and nonwhite, regularly sent money to their parents and one or more of their siblings. As we look at today's prospective teachers, are we considering the economic responsibilities they both have and anticipate having as members of existing families, creators of their own families, aspirants to professional-level education licenses, and aspirants to Greater Boston home ownership?

All the encouragement and recruitment in the world won't foot the bill for these needs and aspirations, as humble and reasonable as they are.

So What's Really Possible?

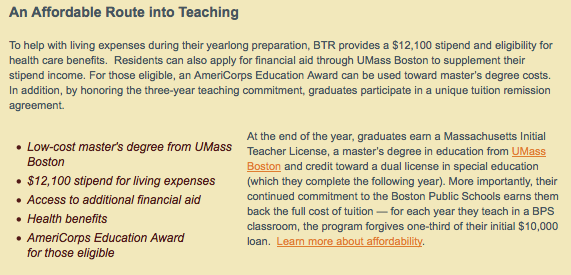

Interestingly, the Globe article ends with descriptions of two programs that offer hope--and ideas that other institutions might learn from. Worcester State University's Latino Education Institute pays students $1000--not a lot, but something "in recognition that many students are struggling to pay for college." And the last paragraph mentions "alternative teacher preparation programs, such as Teach for America and the Boston Teacher Residency program, which have enrollments of people of color of 29 percent and 46 percent respectively." Given the uneven quality and the inadequate post-prep-program support of some Teach for America preparation programs, as well as the significant number of Teach for America program participants who leave teaching quickly, either for other professions or for educational roles outside of the classroom (as reported in the May 2012 issue of the ASCD's Educational Leadership magazine), I am not enthusiastic about Teach for America as the solution to a problem of teaching force diversity.

But if programs like the Boston Teacher Residency program can train teachers while attending to their needs for affordability and can provide intense mentoring and authentic collaboration experience in classrooms during the program year, that seems like a good beginning. That said, I place a lot of emphasis on the word "beginning"--because good teachers aren't created in a single year.

Or even in five years, in my experience. Speaking personally, I would say it took me eight years to become a really good teacher, and that was in a climate and school where there was adequate time and collegial contact to help me grow.

I worry about the kind of support that developing teachers get at schools that are emphasizing communication with parents over communication with students and that are eliminating programs that connect those still-learning teachers with teacher-coaches who have developed skills and tools for helping them to address the needs and challenges that they themselves identify: simply putting teachers together in groups does not guarantee the kind of teacher support that skilled coaches can responsively and effectively provide. In the absence of such programs, I am excited about Massachusetts' having received one of the National Education Association's (NEA's) Great Public Schools Fund grants that can support the development of programs that support teachers to become "top-notch" with the help of colleagues with whom they work every day. If such programs can offer opportunities for growth for both the supported and the supporting educators, gains in professional status, financial rewards, faculty morale-boosting, and authentic connection among colleagues, we may have a shot at attracting and keeping more nonwhite teachers.***

The more we can recognize that the diversifying of the Massachusetts teacher force depends on one or more of the following--

- financial support and incentives;

- post-collegiate educational support and incentives;

- school-based professional support and incentives;

- schools' and districts' active (vs. philosophical) commitment to the idea that top-notch teachers must and can only develop over time; and

- schools' and districts' active (vs. philosophical) commitment not just to diversity as a demographic reality, but to understanding the experiences of, and supporting, their nonwhite students and staff members

Why not go for what we really need--a cadre of nonwhite "top-notch" teachers? We really could achieve this. But encouraging and recruiting in the absence of addressing economic, professional, and cultural factors won't suffice.

* Screen shot from <http://www.newseum.org/todaysfrontpages/hr.asp?fpVname=MA_BG&ref_pge=lst>

** I wish I knew how to interpret the Asian data economically: I don't know in which economic categories Asians are proportionately or disproportionately represented.

*** I believe we need to think about the particular kinds of connections and supports nonwhite teachers might need or want as members of faculties that are predominantly white.