So already, a couple of Saturdays ago when I walked into my husband Scott Ketcham's studio in Rockland, Massachusetts, I fell in love with the first painting I saw. Was it the figure's benign facial expression and gentle, self-effacing, down-tilted gaze? Was it the humble way she seemed to be bearing or even offering a bird's nest, a place of natural protection and birth? Or was it the painting's palate--the vivid yet shadowy magentas and periwinkles that made her flesh and the space behind her distinguishable but inseparable?

When I suggested to Scott that I saw a bird's nest, he made no reply: from his perspective, the authority for what is seen in a painting always resides in its individual viewer. But if you're someone who knows that I usually publish a blog about his most recent work just weeks before his annual open studios--scheduled this year for Saturday, November 19 and Sunday, November 20--you also know that I can't resist identifying, interpreting, seeking patterns, and highlighting moments of comfort and understanding as I confront so much that disturbs or baffles me, as beautiful as I can see that it is.

With Flora in mind, I thought of a recent Scott painting full of fairest flowers. The figure in it gazes somewhat vaguely, perhaps oblivious to the sunflowers that frame her, or perhaps fully immersed in their summer glory. If she is musing on something else or on nothing--which would distinguish her from the woman in the first painting who holds the bird's nest tenderly--what transpired shortly before the moment of the painting? What untold backstories explain why various figures in Scott's paintings seem to have withdrawn at least somewhat into their own private worlds?

This kind of mystery and ambiguity, which I enjoy encountering when I look at many of Scott's works, contrasts with at least two varieties of mystery and ambiguity:

• It contrasts with  the resolvable mystery initially created by "Primavera." Who are the people gathered in this painting, created to a be a prominent Italian groom's wedding present to his wife, and why are they here together?*** So the scholars asked, and learned. Flora and the scantily clad, aggressively pursued figure to her left are actually the same person: the goddess-nymph Chloris, whom we see here in the process of being abducted and raped by Zephyrus, eventually marries him and becomes known by her Roman name, Flora. According to Ovid, she is happy in her marriage. Hmmm . . .

the resolvable mystery initially created by "Primavera." Who are the people gathered in this painting, created to a be a prominent Italian groom's wedding present to his wife, and why are they here together?*** So the scholars asked, and learned. Flora and the scantily clad, aggressively pursued figure to her left are actually the same person: the goddess-nymph Chloris, whom we see here in the process of being abducted and raped by Zephyrus, eventually marries him and becomes known by her Roman name, Flora. According to Ovid, she is happy in her marriage. Hmmm . . .

• It also

contrasts with the bizarre mystery conjured by some of Scott's more

abstract, less traditionally portrait-like paintings. One of Scott's shock-and-awe

painting depicts a female figure emerging from the head of a bull. The

bull's horns are menacing. The eyes we can see clearly are the bull's, and they

shine blank and bright--or are they a little sad and spent? The bull's head seems shaped like a mermaid's

tail.

Is the figure destined to be part-human/part-animal? Or is she emerging into full humanness? With her body

stretched upward and her crossed arms framing her head, she seems

triumphant, despite those horns that are perilously close to her breasts. We can't see her eyes, but the stern concentration of her gaze

suggests she's completely engaged in the process of emerging. But what

will happen to her next? While some of Scott's paintings raise

questions of what happened before, others make us

wonder what will happen next.

But truthfully, if there are stories that Scott's paintings tell, they're more existential than individual. Though there's action in some of them that suggests chronology and cause and effect, I believe they pose broader questions of meaning more than they raise circumstantial, painting-specific questions. As I looked at three very different paintings, all dominated by the color red, I found myself thinking of the title (translated from the French) of Gauguin's huge famous painting in Boston's Museum of Fine Arts: Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?

The first of them terrified me: was this crouching creature human? Was it perching on something courtesy of an outsized talon? Or growing tree-like out of a bulbous clump of roots? Was it in an early or late stage of development, pre-natal or post-natal, or even post-mortem? Could it think? feel? Was it free? In pain? And were those black sockets seeing eyes? If so, did they want to see? Whatever was Scott thinking as he painted this rorschach-esque creature--or did its consciousness or unconsciousness guide him?

The second one I loved immediately because of the serene face of the woman and her obvious love of the sphere in her hands, which I immediately understood as the head of someone she loved deeply. Even when I realized that I actually didn't know what she was holding, her tender and exclusive focus on it soothed me. And my positive feelings stayed intact even when I realized that the sphere seemed to be an outgrowth of the innards of her body. Despite this very strange possibility, her loving gaze kept me loving this painting.

The third one made me laugh, though it distinctly disturbed me. Was this figure with her Mickey Mouse-ear hairdo crazy or feigning crazy? Her eyes were open, I was sure, but was her gaze directed or blank? This painting more than the previous one seemed to have a story behind it: where was she--in some Bedlam-like institution? And what had brought her to this place and state? Whatever the case, she looked like she was about to spring, and I didn't want her to spring toward me.****

Interestingly,

the model in this third painting is also featured in a much more representational painting

that Scott will also be showing in a couple of weeks. In it, she extends a confident, provocative sexual invitation--I love the forward slope of her right shoulder and the easy way her hand rests suggestively in

the black crevice in the foreground. She's one of the few figures in Scott's new work who gazes directly at the painting's viewer, perhaps because she is clearly seeking a reaction and connection, though she's sure to control whatever interaction follows it.

But where are these figures, and where do they come from? Do they live primarily in Scott's imagination and then in our own after we encounter them? And if they emanate from inside us, or summon that which does, what answers to Gauguin's three questions do they suggest?

I don't know, but in a number of instances, even when the central figure has no eyes at all, the painting's mysteriousness is soothing and familiar, shadowy rather than monstrous. One of my favorite of such paintings is monochromatic, soft, and gentle, somewhat domestic if abstract. I don't know what the figure is tenderly looking down on, tending gently, cherishing connection to, but the relationship between her and it seems real, intentional, and loving.

Similarly in this next painting, arresting with its vibrant red and blues, the Rapunzel-like figure--her black hair gleams red and then whirls around to become the glossy, swirling bowl-- seems to be relishing the evolving, circular presence taking shape against her smoothing hands and forearms. What exactly is it? It gleams like a bowl of glossy, sweet red frosting--which is perhaps the most naive way I might describe this highly inviting red hollow that conveys both fullness and a waiting to be filled. She and it together invite, despite--or maybe because of--her downcast gaze. I'm also fascinated by her crossed arms: not only do they chastely cover her breasts, conveying a modesty that partners naturally with her voluptuous sexuality and fertility, but in terms of form, they suggest the eternal and the infinite, echoing the symbol for infinity. What is going on in this painting has always gone on and always will go on, in the world, and in painting. It's in Scott's paintings, and in Botticelli's.

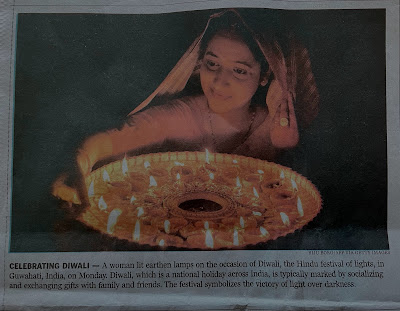

And what's eternal, ongoing, and infinite is not just a content thing. On October 25 while reading the Boston Globe, I came upon a photo**** related to the celebration on Diwali, a national holiday in India, the day before. There was a beautiful, serene young woman, her headscarf gracefully extending along her arm, which lovingly curled around a flat, round dish holding many candles upon which her eyes gazed with so much pleasure. There was that same form, the product of the graceful circling, that I'd seen in various ones of Scott's paintings.

And do eyes ever not matter in terms of conveying emotion and thought, in terms of pushing the inner outward? Our human natures predispose us across time and space to engage with our own experiences and Gauguin's questions as we seek meaning. As we wonder and wrestle, others' eyes sometimes entreat us, sometimes inform us, sometimes excite us, sometimes dismiss us, sometimes baffle us. In response, our own eyes often reveal us, whether or not we want to be revealed.

There's a lot to wonder about, and Scott's paintings, with their abundant light, darkness, beauty, and love served up with compelling ambiguity, fuel that wondering. Come see with your own eyes at Scott's open studios***** (part of the 4th Floor Artists Open Studios).* A madrigal composed by John Wilbye.

** Spring (Primavera). Detail: Flora on Arthive https://arthive.com/sandrobotticelli/works/536246~Spring_Primavera_Detail_Flora

*** File on WikiMedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Botticelli-primavera.jpg from http://www.googleartproject.com/collection/uffizi-gallery/artwork/la-primavera-spring-botticelli-filipepi/331460/

**** The Boston Globe attributed this photo in its print edition (p. A4) to Biju Boro affiliated with Getty Images.

***** Scott's studio is located on the fourth floor of the Sandpaper Factory at 83 E. Water Street in Rockland, MA. Scott's web site is https://www.scottketcham.com/. It should be updated with his newest work by Monday, November 7.

the resolvable mystery initially created by "Primavera." Who are the people gathered in this painting, created to a be a prominent Italian groom's wedding present to his wife, and why are they here together?*** So the scholars asked, and learned. Flora and the scantily clad, aggressively pursued figure to her left are actually the same person: the goddess-nymph Chloris, whom we see here in the process of being abducted and raped by Zephyrus, eventually marries him and becomes known by her Roman name, Flora. According to Ovid, she is happy in her marriage. Hmmm . . .

the resolvable mystery initially created by "Primavera." Who are the people gathered in this painting, created to a be a prominent Italian groom's wedding present to his wife, and why are they here together?*** So the scholars asked, and learned. Flora and the scantily clad, aggressively pursued figure to her left are actually the same person: the goddess-nymph Chloris, whom we see here in the process of being abducted and raped by Zephyrus, eventually marries him and becomes known by her Roman name, Flora. According to Ovid, she is happy in her marriage. Hmmm . . .