But very late Thursday afternoon yesterday, en route to a meeting on Chestnut Street, I was moving along Brookline Street on foot and toward the river--which meant that for the first time in a long time, I could look around and see what was happening along the street.

But very late Thursday afternoon yesterday, en route to a meeting on Chestnut Street, I was moving along Brookline Street on foot and toward the river--which meant that for the first time in a long time, I could look around and see what was happening along the street.It was one of those perfect late spring days when the sky lacked clouds, the air lacked humidity, and the trees were newly but fully hung with the greenest of leaves, thanks to spring's plentiful rain. The sun was warm but not hot; the shadows were poised to lengthen and deepen. Against the haze-free blue sky, the dogwood blossoms, at their peak, gleamed in proud, unabashed whiteness.

It was dogwood awe that got me peering into front yards, backyards, side yards, and courtyards along Brookline Street--and noticing how many of those yards belonged to recently renovated old houses and relatively new housing complexes. This was a new version of Brookline Street, a more well-heeled version of its older, eclectic self in which the industrial and the residential, the humble and the grand, co-existed in a friendly patchwork.

What seemed to have remained constant, however, was the abundance of parks along its length. I believe I counted three public parks, and there may be more than that. Residential areas abut industrial ones in most parts of Cambridge, and the city's public natural spaces continue to play an important role in keeping the city a place first and foremost for people, not industries, not businesses, not even universities.

|

| Is that a face on that tree on the far left? |

|

| If only I could add a picket fence to this picture! |

The two-fold answer to my question came to me the next day and the next night.

The first half of the answer brought me back to my obsession with E.M. Forster's Howards End a few years back. It's the wych elm in the yard of the home much loved by the first Mrs. Wilcox that gives Margaret Schlegel, the second Mrs. Wilcox, peace, deeper understanding, even companionship:

"[The old place] . . . was English, and the wych-elm that she saw from the window was an English tree. No report had prepared her for its peculiar glory. It was neither warrior, nor lover, nor god; in none of these roles do the English excel. It was a comrade bending over the house, strength and adventure in its roots, but in its utmost fingers tenderness, and the girth, that a dozen men could not have spanned, became in the end evanescent, till pale bud clusters seemed to float in the air. It was a comrade" (Forster, 206).**Margaret has purpose: throughout Howards End--the novel, not the movie--she is "attempt . . .[ing] to realize England" (204), seeking to understand its present and past, and to trust in its proud, positive future. This involves both loving and loathing England, grappling with its intertwined shameful and glorious truths--being the kind of Englishwoman who embraces her own undeniable Englishness and leads her life in part for the sake of England's yet-to-be-fully-realized promise, understanding full well its serious failures.

|

| The 2017 Kimbrough Scholars*** |

While the study of history and narrative is central to the CRLS-based seminar that the Kimbrough Scholars take, the question that always accompanies their work and the committee's efforts to support them is "What can (and must) we and others do so that America fulfills her articulated promise of equal rights for ALL of her citizens--the 'we' of 'We the People'?" The adult members of the committee, the student Scholars--we're all engaged in "attempt . . .[ing] to realize" America.

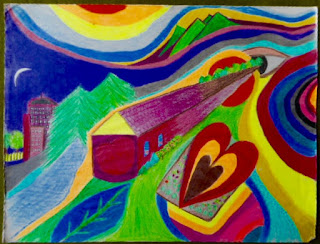

The second part of the answer to my question came to me when I realized how much I wanted to hold onto that fragrant image of lit dogwood and picket fence. It was late at night when I remembered a drawing that I, who seldom draws, had made probably more than twenty-five years ago. That long ago summer, I'd spent some time drawing on the picnic bench that sat near the quiet dirt road that ran by an old friend's now-sold family farmhouse in Bethel, Maine.

I dug out the drawing this morning--finally found it in a carton I'd forgotten I'd stored carefully in my front hall closet. If you look closely on the left-hand side of the drawing, you can see those green, moonlit trees beyond that out-of-scale picket fence.

Also the lights of a city near a river.

All these years later, this picture still speaks to me. But it doesn't tell me anything about America beyond my personal sense of its vastness and movement and endless flow and variation. Or does it? It must not and cannot be only history and politics and economics that lead us to make sense of the story of America and write its next chapters.

I'm curious, Readers: have any of you read any books, particularly fiction, with characters determined to "realize" America, especially female characters determined to do so, and especially female characters who more or less stay put over the courses of their lives? If you have, please tell me about them.

I almost drove to my meeting the other night. I'd probably have come through Boston and driven just a block or two on Brookline Street before turning onto Chestnut. I'm so glad that instead, I took the part of the road I don't usually travel and had the chance to walk through Cambridgeport and America in springtime. That did make all the difference, at least to me.

* Correct me if I'm wrong!

** Forster, E.M. Howard's End. New York: Vintage Books, 1921. Print.

*** Photo by Kathleen FitzGerald, a Kimbrough Scholars teachers.