So already, a week into

2022, I opened The Boston Globe and

saw the capitalized word “MONSTER.” It was in the middle of a half-page ad thanking

contributors to the paper’s annual Globe Santa fundraising drive. Globe Santa provides

gifts for many Greater Boston children who might otherwise receive no presents at

Christmas. Monster, a global job application business and platform, was

among the corporate contributors being thanked.

Had I not just

finished Tiphanie Yanique’s novel Monster

in the Middle, and were I not partway through Joy Harjo’s memoir Poet Warrior, I probably wouldn’t have

paid any attention to “MONSTER.” But

both books contain powerful “monsters” that must be reckoned with, so monsters

were on my mind.

In Poet Warrior, the “monster” designation

carries with it a sense of threat. Harjo uses it in relation to her stepfather,

explaining that she “can’t sleep because I was trying to keep away from the

monster now married to mother,” and also to people and forces that drove people,

including her own Muscogee people, from their homelands (68). As she explains

in “Sunrise,” the poem that opens “A Postcolonial Tale,” the third section of

the book,

We

struggled with a monster and lost.

Our

bodies were tossed in a pile of kill.

We

were ashamed, and we told ourselves for a thousand years,

We

didn’t deserve any of this— (99)

The encounter

with the violent-displacement monster didn’t just shame and kill the vanquished

“We” who speaks in this poem; it dominated its thought and conversation for “a

thousand years.” We’s shame and anger had to have begun being passed from

generation to generation long before the European colonizers and settlers

arrived in the Americas.

Was there

always a monster? Is there always a monster?

For the

father of Stela, the female main character in Yanique’s novel, there is always

a monster. Or rather, there are always monsters. Some of them are human—“For

even [my mother, your grandmother] . . . is a monster—and her mother, too,” he

tells Stela (134). And some aren’t: winter is a “Cold monster” (134).

More

importantly, they are everywhere at every moment.

The

story of the monster on my back, the monster on your back, is not just one of

fathers and daughters but also mothers and sons and mothers and daughters and

even grandparents and aunties and first loves and second and third loves and who

knows what else. It’s all there. Meeting you in the middle, . . . Where you

always are. This is how the whole of history works, sweet girl. And you and me

and the whole of us, we aren’t anything separate from history. (138)

Harjo would

concur with Stela’s father’s thoughts about history and people’s need to live

in connection to it.

But if

monsters run rampant through Stela’s father’s remarks to his daughter, so too

does gratitude. Sometimes, the two are linked, as they are in his recollection

of his first night in the military: “That night, I shivered. So loudly that a

bunk mate threw his blanket on me. Thank you, mate monster. Generous monster.

Thank God” (135).

Harjo also

expresses some monster gratitude. Monsters are not as ubiquitous in her world

view as they are in Stela’s father’s, but stories are always important to her,

as are dreams and spiritual life:

|

. . . Jo Jette says, writing about Medusa

|

I

did not ask for this stepfather. . . . I do not want his story here with mine

even now. Yet he is probably one of my greatest teachers. Because of him I

learned to find myself in the spiritual world. To escape him I grew an immense

house of imagination. . . . I found the ability to construct dreams with many

kinds of materials. I saw the future; I saw the past. I battled monsters, then

sat with them at the table to hear their stories. Everyone has a story. Even

the monster has a story. (92-3)

“Sunrise” also

takes a restorative, life-affirming future-oriented turn, but without going so

far as to give thanks to the monster.

And

one day, in relentless eternity, our spirits discerned movement of

prayers

Carried

toward the sun.

And

this morning we were able to stand with all the rest

And

welcome you here.

We

move with the lightness of being, and we will go

Where

there’s a place for us. (99)

After

centuries of pain and anger, a day arrives on which We experiences a shift in

perception and purpose; soon thereafter, on “this morning,” We acts in new

ways, even foresees and plans. The same could be said for Harjo's Native American artistic community:

As we discussed among ourselves, we began to

consider ourselves to be a king of hybrid: not the confused, worn-out trope of

Indians caught between two worlds, but committed artists rooted in our

individual tribal nations who created with a dynamic process of cultural,

conceptual interchange of provocative ideas, images, and movements. (104)

The monster has ceased to be in control, a

wonderful development, but hardly an easy one. We’s ruminations during

“relentless eternity”--or the years of feeling the pulls of tradition and change, in the case of Harjo and her fellow artists--must have seemed arduous and endless, a steep, necessary price

to pay for deliverance.

Are monsters

just one more example of those things that, if they don’t kill us, will only make

us stronger? Would we be lesser human beings if we didn’t encounter monsters

and somehow manage to defang or otherwise handle them? After some thought about

heroes and monsters in mythology, I wondered if the origins of the word

“monster” might help answer my two questions.

The Online Etymological Dictionary provided

the following information:

|

From the Urban Dictionary

|

early

14c., monstre, "malformed animal or human, creature afflicted with a birth

defect," from Old French monstre, mostre "monster, monstrosity"

(12c.), and directly from Latin monstrum "divine omen (especially one

indicating misfortune), portent, sign; abnormal shape; monster,

monstrosity," figuratively "repulsive character, object of dread,

awful deed, abomination," a derivative of monere "to remind, bring to

(one's) recollection, tell (of); admonish, advise, warn, instruct, teach,"

from PIE *moneie- "to make think of, remind," suffixed (causative)

form of root *men . . . "to think."

The

information about the Old French and Latin origins of “monster” didn’t contribute

much new to my thinking. I’d already understood from ancient literature that a

monster’s physical malformation, cast upon it at or before birth, marked it as

the harbinger, if not the agent, of god-anticipated and even god-sanctioned

suffering and adversity. Poor monster, as Stela’s father might have said.

|

"Landed Like Icarus" by Scott Ketcham

|

But

the information about the PIE (Proto-Indo-European) roots of “monster” did

offer me something new—the idea of monsters being more for us than against us. Could

our encounters with them serve to “admonish, advise, warn, instruct, teach” us?

Could their function be “to remind” us of

what we already know somewhere deep inside but have managed to forget?

The

notions that we humans easily become estranged from what know and that it takes

either effort or crisis to return us to that knowing is at the heart of several

religious traditions. A monster can be or can precipitate the crisis that leads

us back to knowing and, in so doing, leads us forward. Clever, helpful monster,

Stela’s father might have said.

And

Harjo would probably have agreed. But she also would have reminded him of how

terrifying, prolonged, destructive, and sometimes fatal struggles with monsters

can be. Monster encounters might yield wisdom, but we’d crazy to seek out

monsters. If anything, we should feel relieved and fortunate when they don’t

set their sights on us.

Still

curious about Monster, I called the company to ask about its name. While there

are imagined evil creatures of all shapes and sizes, monsters are often envisioned

as the largest. Was the name "Monster" simply meant to convey that the company

was global and huge?

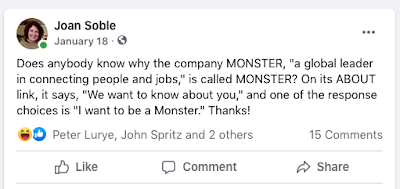

When

no one at Monster answered the phone at the number given on the company

website, I turned to Facebook and Twitter; perhaps of my friends or contacts

could explain its name.

First

to respond on Facebook, my businesswoman cousin theorized that Monster was so

named because, like the Sesame Street cookie monster, it had aimed to gobble up all the cookies—the smaller job

application companies—in the cookie jar.

But a

little later one of my former students posted the real answer:

"Yes. . . . when [Monster] came out (and of course, I was

there at the time), it was a hip and suitably wacky and irreverent name. Like

Yahoo! or Google (then known as a play on googol). It had that fun Pixar-style

mascot. Looking for work is fun and wacky! The idea didn’t age well. On the

other hand, it outlasted thousands of contemporaries, so… "

So

Monster’s founders weren’t trying to stress the advice-related aspects of the PIE

roots of “monster”; they were just being unbelievably hip and trendy.

A few

comments later, a Facebook friend thirty years my junior reminded me that people

raised on Sesame Street were more apt

to find monsters “cute or funny” than to fear them. Shades of all those

Brothers Grimm fairy tales that were purged of their most gruesome,

fear-inducing original elements. Meanwhile, my cousin’s cookie monster analogy was

even more apt than she knew.

A couple of weeks after I saw MONSTER in the newspaper, the word

“monster” appeared again--on Wednesday, January 19, this time on the front page.

The governor of New Hampshire had used it to refer to the father of missing

seven-year-old Harmony Montgomery (Say her name). Adam Montgomery, currently in

jail, has “a violent history” and “previous convictions including [for]

shooting someone in the head and a separate attack in two women.” Montgomery

sounds like a far more deadly monster than Harjo’s stepfather.

The

January 19 Boston Globe reminds us

again there are always monsters. In the adult world, they vary from “wacky and

irreverent” to the last thing you’d ever wish on a fellow human being. They’re

not always people, though it’s usually people who create them. And it’s usually

people whom they afflict. They exist in the eye of the beholder, sometimes the

eyes of multiple beholders, and they are real.

The unwelcome

ones that show up complicate our lives, knocking us off course. Sometimes they

challenge us to survive or evade or defang them, as Joy Harjo’s did; other

times, they challenge us to acknowledge or even integrate them into our selves

and worlds, as Stela’s do. When we’re lucky, we learn from monsters, but the

learning is always hard—often too hard, too exacting.

We’re better

off not seeking monsters. Besides, they will find us anyway. If we’re lucky,

they’ll be the kinds that are more interested in our cookie jars than in us.

Arnett,

D., & Koh, E. “Sununu Points to Mass. in Girl's Case.” (2022, January 19). The

Boston Globe, 19 Jan. 2022, pp. 1, 8.

Harjo, J. (2021). Poet warrior: a

Memoir. W. W. Norton & Company.

Monster.

Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved

January 18, 2022, from https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=monster.

Monster.com. In Wikipedia.

https://www.immagic.com/eLibrary/ARCHIVES/GENERAL/WIKIPEDI/W110114M.pdf

Soble,

J. (2022, January 18). Does anybody know why

the company MONSTER, "a global leader in connecting people and jobs,"

is called MONSTER? On its [Comments on status update]. https://www.facebook.com/joan.soble.1. Yanique,

T. (2021). Monster in the middle. Riverhead Books.