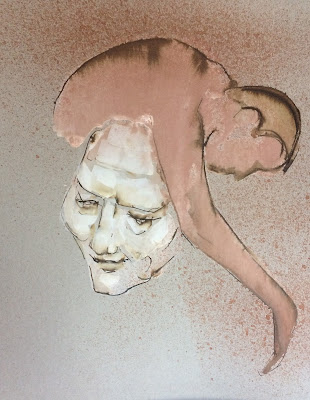

So already, throughout the pandemic on Monday and Tuesday nights, bolts of imagination have streaked across the cybersphere toward my cellphone. At around 10:15, a telltale “ping” generally signals that my husband Scott* has just messaged me a few photographs of drawings he’s done that night in his studio.

Though Scott generally describes himself as a painter, he has drawn more than painted during the pandemic when models, for the sake of everyone’s health, have had to Zoom into this studio/online classroom rather than pose breathing, masked, and life-sized before him. Frequently, the models do “short poses”—maintain the same pose for no more than ten minutes—which means that most of Scott’s drawings are “finished” first drafts that he immediately sets aside to move on to the next act of creation.

Drawing in this way, Scott doesn’t have much time to think or plan; what happens on his paper is the result of a quick, wordless interaction among his eye, his brain, his hand, and, of course, the observable something the model presents to all three. On the occasions I’ve asked him what he’d been thinking while drawing a particular drawing—please note, I’ve just used “drawing” as both a noun and a verb—he’s told me he wasn’t thinking. On some level, I can believe that. Then again, in his quest to get me not to over-think, he often tells me he’s not thinking.

Recently, I’ve been wondering about the sources of drawings, Scott’s and other people’s. Because often I’ve used the words “draw” and “drawing” multiple times in the same sentence as I’ve been trying to formulate my questions, I’ve started thinking about those words themselves. In other words, while being drawn to understand from where artists’ drawings are drawn, I’ve become curious about the word “drawing” itself.

So a few observations about the drawing-related innards of my last sentence. First, my first “drawn” and my second “drawn” don’t mean precisely the same thing. Second, “drawings” is a plural noun denoting the products of the activity of “drawing”—a gerund. Third, there are a couple of conspicuous usage absences in this sentence, in particular those of the present participial (drawing) and past participial (drawn) forms of the verb “to draw,” as used to convey the act, present or past, of making a sketch or picture.

I know; my observations—even of what’s not there—seem so nerdy and nitpicky. But I love thinking about words’ meanings, etymologies, and uses—not a surprise, given that I am a Jewish retired English teacher who writes blogs and poems. So many words in Jewish texts are imbued with multiple layers of meaning**, inviting all to wrestle with their potential to open doors to the often elusive combination of divine connection and personal possibility and responsibility. In this context, words are like rabbit holes (or rabbi holes!), drawing us down into their fruitful complexity before, ideally, releasing us to the everyday, above-ground world with a greater sense of something simultaneously focusing, enlarging, and galvanizing.

When I sat down the other day to begin writing

about “drawing,” I named my Word document “Drawing Itself”—just to distinguish

it from anything I might write about particular drawings. But the minute I did

that, my inner grammarian wondered, “Who or what is (or was) drawing itself?” That added another layer to my questioning.

With all of these things in mind, I began thinking about the range of things that people draw. They don’t only draw pictures. They also draw blood, water, raffle tickets, swords, and guns—lots of physical things, including, on some occasions, lots. In addition, they draw mental things such as distinctions, conclusions, blanks, and lines (in the sense of “the line” when they’ve had enough of something or someone).

Then there are the things that draw people, allowing them to describe themselves as “drawn to” or “drawn by”: the edges of cliffs or water, their soul mates, street musicians playing with feeling and skill, politicians making promises, great-looking shoes in a store window, three-layer chocolate cakes or thick slices of watermelon sitting on a counter.

I had a fleeting “world peace” thought as I contemplated these disparate items and ideas: wouldn’t it be great if when people drew guns, other people thought only to draw near in order to see how those guns were being sketched?

As the active and passive uses of “draw” multiplied in my mind, I headed to the Word Hippo web site to find all its definitions, and then to the Online Etymology Dictionary. The Word Hippo*** web site, with its almost two pages’ worth of definitions, nearly overwhelmed me with all of the ways and places the word could be used. But the Online Etymology Dictionary**** quickly refocused me.

According to the OED, drawing in the sense of making pictures was called “drawing” because one essentially dragged or pulled, thus drew, a pencil, crayon, or other implement across a piece of paper or other surface that retained its mark. That use of the word dated to roughly 1200. The use of “draw” to describe the pulling motion one used to remove a sword from its sheath was slightly older, dating from the late twelfth century. Quickly I understood that “The pen is mightier than the sword” worked even better than I’d ever thought or taught. It didn’t just symbolize the functions of two similarly shaped objects to create an excellent example of metonymy; the pen and sword were also connected because both were actually physically wielded—drawn—in similar ways.

Still, that information about the physical

motion of drawing didn’t help explain individual drawings’ sources and

inspirations. I thought about Scott, how seriously he takes drawing; he might

even be lost without it. That thought focused me on the two items on my list

most critical to life itself, water and blood. The Word Hippo web site defines “lifeblood” both literally and

figuratively, offering as its figurative definition “That

which is required for continued existence or function.”*****

Still, that information about the physical

motion of drawing didn’t help explain individual drawings’ sources and

inspirations. I thought about Scott, how seriously he takes drawing; he might

even be lost without it. That thought focused me on the two items on my list

most critical to life itself, water and blood. The Word Hippo web site defines “lifeblood” both literally and

figuratively, offering as its figurative definition “That

which is required for continued existence or function.”***** Wikipedia says that the two hands in Escher’s “Drawing Hands”*(7) are engaged “in the paradoxical act of drawing one another into existence.”*(8)

Do we create ourselves by creating? If we do, I suspect it’s generally a private affair. Meanwhile, our creations, once loosed into the world, have their own lives beyond us, meaning whatever they mean to those who experience them. I can't say that they're experiencing us to any significant degree just because they're experiencing our creations.

Frankly, I'm pretty sure these questions and my musings wouldn't matter much to Scott, though they'd interest him: he is, understandably, too busy

engaging with his imagination and materials--making art, not thinking

about why or "why this." But they do matter to my non-artist self. I believe that when we are fully engaged in creating, whether we're drawing or writing, we experience ourselves, drawing from ourselves as we necessarily do. And experiencing ourselves is important.

Hi Joan -- Another enjoyable and thoughtful read – and I love the Escher drawing included -- Thanks! -- Hope you do not mind if I add to your ‘range of things that people draw….”-- from the world of Curling, -- Curlers often refer to ‘draw weight’, as we attempt to deliver our stone so it ends up in the ‘House’ -- which is our target – often easier said than done !!

ReplyDeleteThanks, Peter, for reading and responding--and especially for adding to my knowledge of drawing's many uses.

Delete