Today, having finished this book, I am fulfilling that promise. As you can imagine, I've been thinking a great deal about Sabbath historically, religiously, and personally in these last weeks.

I encountered Shulevitz courtesy of a show hosted by Ezra Klein: Shulevitz was Klein's guest in January, and at a friend's suggestion, I listened to it--well, actually, downloaded and read the interview transcript. That interview led me to a rereading of Abraham Joshua Heschel's The Sabbath, a first reading of Shulevitz's book, and then a rereading of the interview transcript.

Why the rereading of the interview? Because I sensed that something had changed in Shulevitz's own "Sabbath life" between 2010 when she'd written the book in and 2023 when she was talking about it with Ezra Klein.

Just to be clear, more than a spiritual autobiography, The Sabbath World is a cross-cultural, cross-religious history of the concept of Sabbath and the practices and requirements associated with it.

As a result of reading it, I

have new and deepened understandings of Sabbath's "development" and differentiation over time. For example, while I always understood that "Remember the Sabbath

day, to keep it holy" urged the distinct separation between the first six

days of Creation and the seventh, I now understand that various religious and

political leaders over many centuries urged the distinct separation between Jewish and non-Jewish--though not necessarily Christian--Sabbath observance. The book also reminded me that Sabbath observance, like virtually everything else Jewish, varies for different Jewish individuals and groups.

Thanks to Shulevitz, I also now know more about Transylvanian Unitarians, Anabaptists, and Puritans than I ever did before, and I understand that the original rationale for today's abundant Sunday afternoon concerts and other artistic performances was much more about improving "other people" than profiting off the general population's interest in entertainment, distraction, and enrichment.

But despite its offering plentiful historical and sociological nuggets, The Sabbath World is still in part a spiritual autobiography, as Shulevitz reminds us in the opening sentences of the book's final section (211).** Anticipating her readers' wanting to know how she keeps the Sabbath "now," she explains, "I

have not changed all that much [in how I keep the Sabbath], and

everything has changed for me" (211). What I couldn't tell was what that "changed everything" was beyond her much enlarged understanding of Sabbath's development and differentiation.

I got excited when in that same paragraph she admitted that "I still like the idea of the fully observed Sabbath more than I like observing it," since I could recognize similar feelings in myself.

But two pages later when she defined God as "the ungovernable reality commemorated by ritual" (213), I felt her retreating back into brainy historian mode, and I was disappointed that most the book's final pages were devoted to a dispassionate analysis of the costs and benefits of ritual.*** On the basis of that analysis, she seemed just a little too ready to distance herself from her longing for Sabbath ritual and observance. The mind and the heart don't always walk hand-in-hand.

What I had liked about her Ezra Klein interview--and maybe it was because he was particularly interested in the whole question of how a Jewish person observes the Sabbath while the other inhabitants of dominantly culturally Christian America go about their busy Saturdays--was that Shulevitz seemed to know just when to apply her vast knowledge of the Sabbath to his question. Maybe I was finally seeing the "everything changed for me" aspect of her experience that I hadn't grasped while reading her book.

The best way I can think of to tell you how this interview helped me approach Sabbath observance is simply to quote from it and offer an occasional comment****:

• In response to Klein's question "'What are the Sabbath rules attempting to

create?" Shulevitz explains,

"'I would argue that they're trying to create

meaning. I think of all the rules around the Sabbath . . . as creating a

kind of frame, . . . you could think of it as a proscenium around a

stage, or you could think of it as a break after a line of poetry.'" *****

Because I like to read and write poems, I was taken by her line break

metaphor: a line break separates what would otherwise remain connected and undifferentiated, slows things down, creates a space for breathing, for envisioning, for making meaning.

• Shulevitz's discussion about Sabbath puts at its center God and the created world, not the individual person's--or even the group's--merits and shortcomings. Its focus is not repairing the individual's strained or broken relationship with God and/or other people, though it may have that effect. It's about how "good" Creation, which includes us, is, not how "good" the individual is, can be, should be. It's a day about peace.

"' . . . Sabbath is the time you're supposed to stop acting on the world. . . . You're supposed to let the world rest, as well as you. . . .

"'And then on seventh day, God rests. But God doesn't just rest. He makes rest. . . . God was creating this system of meaning, which is based on stopping and looking back over what God had created to say, is that good? And it turns out it was good.'"

In this context, rest is a state of being, an orientation toward the created world, rather than a primarily self-referential not-doing or not-working. As Klein explains, quoting Heschel,

“'Menuha, which we usually render with

rest, means here much more than withdrawal from labor and exertion.' He [Heschel] goes on

to say it’s something closer to, quote, 'tranquillity, serenity, peace and

repose.' And I want to get at the distinction between rest, as defined by

something you’re not doing — rest is I’m not working — versus rest as a kind of

state I’m achieving."

Shulevitz has come to understand that at least for her, this "state of being" rest cannot be achieved in isolation:

"'And the great lesson I learned from writing this book was, I don't have to yell at myself for not doing it. I can't do it until I become part of a community that does it, that makes rest something pleasurable, that makes it festive.'"

Shulevitz's lesson learned, with its emphasis on the joyful aspect of the communal Sabbath, coupled with her permission to fall short when observing Sabbath in isolation, reminded me of a stanza from the poem "Let Them Not Say" that Jane Hirshfield read on another Ezra Klein show:

Let

them not say: they did nothing.

We did not-enough.

With Shulevitz's and Hirshfield's words in mind, I can aim and aspire wholeheartedly to observe Sabbath without chastising myself for falling short of achieving and maintaining a state of rest--and how much can rest really be rest when it's coupled with the word "achieve"?

• Later in the interview, Shulevitz further developed this idea of the welcoming aspirational Sabbath when she talked about the Jewish idea of holiness (I'm just not sure if her discussion of holiness holds for other religious traditions):

"'One thing I would say about holiness is

it means setting apart and perceiving as special. Certainly in the Jewish

tradition, it is literally conceived as that, which is set apart. So we’ve

already talked about creating these boundaries around time and setting it

apart.

"'One of the things that fascinates me,

and in a way it’s why I called the book “The Sabbath World,” is that it’s a

sort of enclosed world that we can never reach. And holiness is a little bit

like that. It’s this thing that’s beyond us. It partakes of a different order

of being. It’s God’s order of being. We’re never going to get there.

"'The Sabbath sort of has nostalgia for

the pure Sabbath we can never achieve built into it. And this is constant

throughout — the rabbinical legends. There’s a wonderful legend about a Sabbath

river that lies beyond our world. It’s always going to be just beyond our

reach. The perfect Shabbat, the perfect Sabbath — we’re never going to attain

it.'"

This wonderful Sabbath that none of us can really attain, but that we can sense sometimes, that we catch a glimpse of out of the corner of our spiritual eye, that we can experience for fleeting peaceful moments, that we can rest toward (as opposed to work toward) in the company of others or by ourselves--this is the idea I keep in mind that keeps me aspiring.

An important benefit of reading The Sabbath World for me was that it also allowed me push aside the theories and uses of Sabbath that weren't a good fit for me. The book carefully delineates the many theories and uses of Sabbath across times, national boundaries, and religious traditions, some of which were deliberately designed to diverge from anything strongly or remotely Jewish. Consequently, I could recognize a number of non-Jewish Sabbath ideas that are and have been so mainstream in America that they shaped my ideas about Sabbath, even though they conflicted with the ideas of Sabbath I encountered in my Jewish education. Before I read Shulevitz's book, for example, the idea of resting on Sabbath for the sake of recharging, refocusing, and re-inspiring myself in preparation for "the work" of next week or next month completely overshadowed any notion I had of resting for God and in appreciation of Creation.

Essentially, what interests me now is trying to fulfill the commandment "Remember the Sabbath Day, to keep it holy." But unpacking the meaning of that commandment isn't easy.

I have always known that "holy" had many different meanings and criteria for different people. But in these last weeks, I've also been thinking a lot about the word "keep"******--reading its many definitions, exploring its etymology. It can denote observe, but also mean to preserve and maintain, even to safeguard that which might be dismissed, tainted, or destroyed. Shulevitz talks about a revered German rabbi who raised the question of "what is there to safeguard the world from man" and then answered it with "the Sabbath." In this case is that it's the world, not the Sabbath, that needs safeguarding. But maybe both need safeguarding.

I have always known that "holy" had many different meanings and criteria for different people. But in these last weeks, I've also been thinking a lot about the word "keep"******--reading its many definitions, exploring its etymology. It can denote observe, but also mean to preserve and maintain, even to safeguard that which might be dismissed, tainted, or destroyed. Shulevitz talks about a revered German rabbi who raised the question of "what is there to safeguard the world from man" and then answered it with "the Sabbath." In this case is that it's the world, not the Sabbath, that needs safeguarding. But maybe both need safeguarding.

In conjunction with the idea of respectfully "keeping" valuable "things," the idea of covenant has been coming into my mind again and again. To my surprise, I find myself wanting to keep the Sabbath out of my sense that I'm part of a mutual promise and relationship between God and the Jewish people, and in solidarity with other Jewish people also trying to rest in order to keep the Sabbath Day holy.

Trying to keep the Sabbath is getting easier for me. Notice that I said that it's the trying, not necessarily the keeping, that's getting easier. But, as my earlier blog post explained, I can feel myself resting in different places and ways.

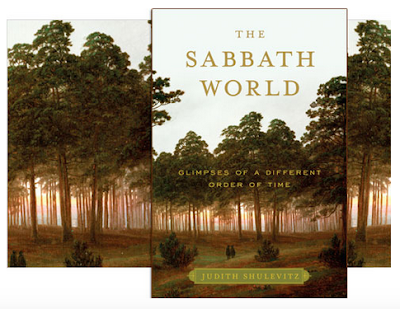

That's why I love the photo of The Sabbath World as it appears on Shulevitz's website--so much so that I'm posting it here again. Its cover photo is more lively and colorful than the one on the book that I purchased; not only does it present a slice of Creation, but it locates in it two companions strolling and being, suggesting that they're experiencing and appreciating both Sabbath's and Creation's peacefulness. Furthermore, the book sits atop a copy of the cover photo, emphasizing both Sabbath's connection to and separateness from Creation. It looks like a good Sabbath to me--a time set apart; an experience of Creation, relationship and rest; and maybe even the opportunity to experience a momentary sense of that Sabbath ever beyond our reach.

All of this brings me back to a poem I met at the end of my junior year of high school and fell in love with immediately, "The Lake Isle of Innisfree" by William Butler Yeats*******:

All of this brings me back to a poem I met at the end of my junior year of high school and fell in love with immediately, "The Lake Isle of Innisfree" by William Butler Yeats*******:

I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made;

Nine bean-rows will I have there, a hive for the honey-bee,

And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow,

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings;

There midnight’s all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet’s wings.

I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart’s core.

You can't clutch at peace, commandeer it, insert it on demand into your busy self- and world-centered life. You can only prepare yourself for it in hopes that when it "comes dropping slow," you can perceive and receive it, and then commune with the gift of it as it reminds you of your inclusion in the transcendent, unified scheme of things. And then, if you're lucky, you'll be able to remember it, to "hear it in the deep heart's core" even when life demands that you traipse the "pavements grey."

I'm trying to give Sabbath the chance to come dropping slow. And I'm hopeful about the prospects of that since I'm thinking about Sabbath more as an opportunity than as a challenge I will probably screw up. I thank Shulevitz for helping me think about how best to create the space-in-time that might let me embrace that opportunity.

* This photo appears on Judith Shulevitz's website on the "Book" link: https://www.judithshulevitz.com/book/.

** Shulevitz, Judith. The Sabbath World: Glimpses of a Different Order of Time. Random House Trade Paperback, 2011. *** Multimedia Artist from Montreal | Valeriya's Art: Multimedia

Artist from Montreal | Valeriya's Art Valeriya Khomar artist in

Montreal creates abstract, contempo acrylics, mixed media paintings.

Custom orders are welcome. Giclee prints are available. https://www.pinterest.com/pin/109001253472030797/

**** Illustration by Sefira Lightstone accompanying Chabad.com article entitled "Shabbat: An Island in Time": https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/253215/jewish/Shabbat.htm

***** Klein, Ezra. “Sabbath and the Art of Rest: Judith Shulevitz Shares the Wisdom of the Sabbath and Its Offering to a Modern World That Struggles to Umplug.” The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/03/podcasts/ezra-klein-show-transcript-judith-shulevitz.html. Accessed 3 Jan. 2023.

*(6) WordHippo definition of "keep": https://www.wordhippo.com/what-is/the-meaning-of-the-word/keep.html

*(7) Photo included in the March 29, 2011 post in the blog A Mountain Hearth: Tale of Modern Homesteading and Modern Adventure: https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjB3tOzhh0eBI2iLCRjExSz5ojF8I5ujvkBKtTRP_2qxTCiFxkc_ODPS6kzIsoqwwtZSVG1PRpSg3t0ITxy-aJtoilAagWRSvBBAPPgZK6ll2yuGHX5fETvd-V93OpVIg-8qeghltZAUKY/s1600/Innisfree+2.JPG

I have always known that "holy" had many different meanings and criteria for different people. But in these last weeks, I've also been thinking a lot about the word "keep"******--reading its many definitions, exploring its etymology. It can denote observe, but also mean to preserve and maintain, even to safeguard that which might be dismissed, tainted, or destroyed. Shulevitz talks about a revered German rabbi who raised the question of "what is there to safeguard the world from man" and then answered it with "the Sabbath." In this case is that it's the world, not the Sabbath, that needs safeguarding. But maybe both need safeguarding.

I have always known that "holy" had many different meanings and criteria for different people. But in these last weeks, I've also been thinking a lot about the word "keep"******--reading its many definitions, exploring its etymology. It can denote observe, but also mean to preserve and maintain, even to safeguard that which might be dismissed, tainted, or destroyed. Shulevitz talks about a revered German rabbi who raised the question of "what is there to safeguard the world from man" and then answered it with "the Sabbath." In this case is that it's the world, not the Sabbath, that needs safeguarding. But maybe both need safeguarding. All of this brings me back to a poem I met at the end of my junior year of high school and fell in love with immediately, "The Lake Isle of Innisfree" by William Butler Yeats*******:

All of this brings me back to a poem I met at the end of my junior year of high school and fell in love with immediately, "The Lake Isle of Innisfree" by William Butler Yeats*******:

When I was a kid the world stopped on the Sabbath, which was Sunday in our house. No stores were open, traffic was light, kids knew to keep their voices below the weekday decibel level, dinner was early and long, and we did rest. Now just about everything is open, mornings are often filled with kids' sports events, and I have to focus hard at finding the quiet. Even Church can be full of clamoring "havetas", pressures to sign up for committees, and to go to coffee hour, wear a nametag, and socialize with The Community. Innisfree does beckon! I want the Sabbath to be like Julianne Stanz's description of prayer in her book "Braving the Thin Places." In her chapter titled "A Pause for Prayer," she writes: "For a long time I thought that praying was something to do. But the heart of prayer is simply being and resting in God. Prayer creates a space for grace in your life." Amen.

ReplyDeleteHi, Susan--Thank you so much for your thoughtful, descriptive comment--which sounds like a poem written as a paragraph. I love the quotation your comment ends with, and I suspect I would enjoy "Braving the Thin Places." I guess some Sabbath nostalgia is as much a personal, "recent" memory as whole group historical-cultural memory. Again, thank you!

Delete